Ben Palmer is Chief Conductor of the Deutsche Philharmonie Merck in Darmstadt, and Founder and Artistic Director of Covent Garden Sinfonia. I was delighted to catch up with Ben and find out how he has built his career as a professional conductor, performing in the Royal Albert Hall, amongst other prestigious venues, and setting up his own orchestra in London.

Tell us a bit about your musical journey growing up…

I started learning the trumpet when I was seven, but didn’t take it particularly seriously until I was 15. That was the year I was given a place in Suffolk Youth Orchestra, and on my first course we played Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. I was so excited after the concert that I couldn’t sleep properly for two nights – from that moment on I was hooked, and decided that I wanted to be a professional musician.

Were you encouraged in your music-making at school?

Very much so. There were lots of opportunities to play and sing, to compose (we did a project with players from the City of London Sinfonia, led by composer Alasdair Nicholson, which was hugely inspiring), and even to take a few sectional rehearsals as a conductor.

When did you first start to develop an interest in conducting?

I took my first real steps as a conductor as an undergraduate at Birmingham University. I’d always been fascinated with the role of the conductor, but at university I started following miniature scores in rehearsals, and began to question the gestures I was seeing and the musical decisions that were being made. I auditioned to conduct in the annual Summer Festival, and gradually started to gather some experience. I did more conducting while I stayed on at Birmingham to study for an MPhil in composition, and then, after I moved to London in 2005, decided to make it my main focus after giving up a PhD in composition at the Royal Academy of Music, just a few months into a three-year course. I then spent the next ten or so years working with my own chamber orchestra, Covent Garden Sinfonia, and conducting lots of amateur choirs and orchestras, and student ensembles, until I began to be offered some more professional work as a guest conductor, both in the UK and abroad. It’s certainly been a long journey (so far – there’s a long way to go yet!), but I’m always grateful for all the experience I’ve had when I meet a new orchestra for the first time.

What was your journey to becoming chief conductor of the Deutsche Philharmonie Merck?

I was driving to a rehearsal in early 2016 when I had a call from the managing director of the orchestra, who explained they were soon to be looking for a new chief conductor, and that they were inviting conductors in whom they were interested, or who had been recommended to them. My name was put forward by mentor, Sir Roger Norrington, for whom I had been working as assistant conductor since 2011. I was invited to conduct the orchestra in July 2016, and then immediately offered a second concert in March 2017, after which I was offered the chief conductor job, and my contract started in September of that year. It’s such a joy to work with what is now ‘my orchestra’, and they’ve been extremely patient with me as my German has improved from lapsed GCSE level to reasonable fluency, albeit with slightly improvised grammar and the occasional word or joke in English!

You often seem to be catching a plane somewhere! How do you manage the travelling/performing/jet lag?

It can be challenging when I’m constantly on the move – especially if I have several projects back-to-back in different cities or countries without the chance to go home in between – but I’ve got the logistics down to a fine art, which means I can maximise time for sleeping and learning scores whilst I’m away. Packing, for example, is very straightforward: when I’m rehearsing I only wear black t-shirts and black trousers, so I just grab the relevant number for how many days I’m away, plus whatever suit(s) I’ll need for the concert(s). I have a big (but very strong and light) suitcase with four wheels, and a huge rucksack that can comfortably carry big A3 scores. (Tip: batons always go in hold luggage, scores in hand luggage!)

I spend a lot of time planning how to get from one place to another, which can be complicated. For example, in December I have a rehearsal on Monday in Manchester, then on Tuesday I fly to Stuttgart and get driven to nearby Reutlingen. All day Wednesday and Thursday morning I have rehearsals, then I fly home to London that afternoon. On Friday morning I’ll drive up to Manchester, conduct a general rehearsal and concert with the Hallé Orchestra, then drive home that night. Very early on Saturday I’ll get an Uber to Heathrow and catch another flight to Stuttgart, where I’ll have a rehearsal and concert with the Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen. On Sunday we repeat our concert in Nuremberg, after which I’ll race to the airport and fly back to Gatwick. Then, somehow, I need to be in Manchester for concerts at 11am, 1.30pm and 4pm – I haven’t worked that bit out yet! Not all weeks are that crazy – very often I’ll be in the same place for a few days or even a week or two. At the moment most of the travelling I’m doing is within the EU (long may we continue to be a part of it – freedom of movement is essential for musicans!), so jet lag isn’t too much of an issue.

Very often, though, I have to get up horribly early to catch a flight at 6 or 7am, to be in Darmstadt or Prague for a mid-morning rehearsal. Those days are punishing, and I’m grateful if I’ve been booked into a nice hotel where I can relax, and FaceTime my wife and 11-month-old baby boy! To be honest, I love the lifestyle, including the travelling, but there are days when I’m desperate to return home to my own bed and my family.

What is your process for preparing to conduct a new piece with an orchestra?

I love buying new full scores and learning new pieces, and will start the learning process as early as I can – sometimes more than a year before I will actually conduct it, although I don’t always have that luxury. Learning a piece, for me, involves sitting at my desk with the score, reading it like a book, absorbing the harmony, structure, phrase lengths, orchestration, and so on. I rarely use a piano or listen to recordings, as I prefer to rely on my own musical imagination to hear the music in my head. I can learn a Haydn symphony in an hour or two, but a Mahler symphony might take me months. If I have lots of time until the performance, I’ll often put the score away for a few months, coming back to it a few weeks before the rehearsals begin. I’m sometimes asked to learn pieces at very short notice, and can absorb most things very quickly when I have to; this is another reason why it makes sense to get ahead of myself with learning the repertoire I know about a long time in advance.

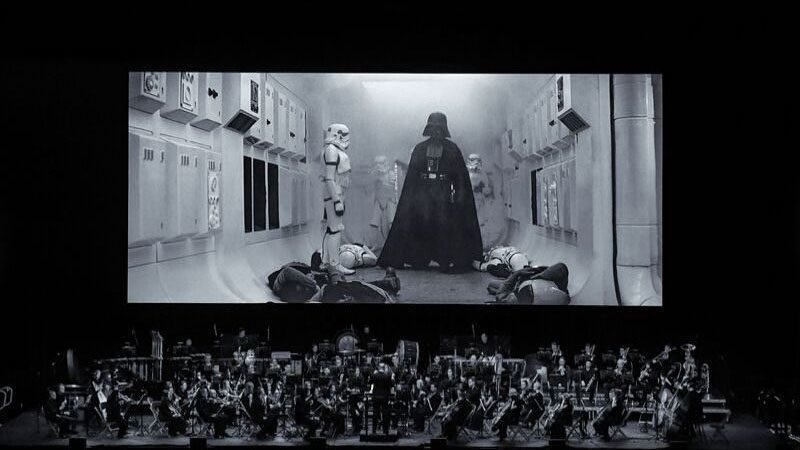

You’re one of Europe’s specialists in conducting live to film. How did you develop this interest and what are the challenges and joys of conducting this type of concert?

I conducted my first film, The Snowman, with own Covent Garden Sinfonia in 2013, and instantly became a bit obsessed with doing it. The precision needed is terrifying – the film won’t wait for me, and I have to hit all the synch points! – and so the preparation element is even more important. The next one we did was Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, then Casablanca, and Psycho. After that I started being invited to conduct lots of the big John Williams films with other orchestras – Jurassic Park, Home Alone, Harry Potter, Star Wars, Jaws, E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark – as well as things like Back to the Future, Casino Royale and The Pink Panther. Each film poses different challenges, mostly to do with the synchronisation of orchestra and screen, but the thrill of getting the big hits in the right place, and amazing reactions from sell-out audiences makes the hard work more than worthwhile.

What skills do you think an effective conductor should possess?

It goes without saying that clear movements and an efficient rehearsal technique are essential. But the most important skill is the ability to listen, and from that to analyse, adjust, and solve problems in real time, usually without using any words.

You’re also in demand as a composer, arranger and orchestrator. How do you find time and space for this, in addition to a busy conducting schedule?

The short answer is that I don’t really have time any more. I only accept one or two composing commissions each year, and it’s a real struggle to find space in my schedule to actually get anything done, not least because I’m painfully slow to compose. Arranging and orchestrating is much easier for me – I’ve been known to do it while watching a film – but I don’t do so much of it any more.

Do you have a typical working day – what does it look like?

A day at home is often a balancing act between the work I love doing – preparing whatever scores I’m working on, and planning future programmes – and what I consider to be the real ‘work’, which usually involves hours of answering e-mails and making calls, scheduling rehearsals, booking flights and trains, and the endless admin of running my own orchestra. When I’m actually conducting, working with an orchestra, I’ll typically have one or two three-hour rehearsals, or a three-hour general rehearsal and concert. This can be tiring, but the adrenaline always gets me through.

What is your proudest achievement so far?

I’m very proud that my own orchestra, Covent Garden Sinfonia, is still in existence more than 12 years after I started it. It’s been very difficult at times to keep it afloat, but we’ve done some amazing projects together, and I hope it’s here to stay. Of course, I feel incredibly fortunate to have my chief conductor job in Germany – more than I can put into words, really. Otherwise, getting to conduct films with orchestra in the Royal Albert Hall has been an unimaginable thrill. The atmosphere is simply amazing, and I’m very proud to be conducting some of my favourite music with some wonderful orchestras there.

And finally…what three tips would you give to any students aspiring to be a conductor?

Firstly, and most importantly, respect your musicians. Never forget that any orchestra, be it amateur, student or professional, represents thousands of hours of practice, and though you may have very strong ideas about how you feel the music ought to go, you should always try to be polite and efficient. Don’t lose your temper, and don’t waste anyone’s time. Secondly, if you make a mistake, admit it. Everyone in the orchestra will know if you’ve put a foot wrong (mis-cued an entry, miscounted a phrase length or beat the wrong pattern, for example) so just apologise and move on. Don’t try to cover it up or blame it on anyone else – you’ll instantly lose the respect of the entire orchestra. Finally, say yes to everything, paid or unpaid, however amateur the ensemble is. Don’t be proud. At the start, what you need is time waving your arms in front of people, learning how to do it, and (more crucially) learning how not to do it. Make your mistakes in situations where it doesn’t matter, and when your chance comes, you’ll be grateful you’ve had that experience.

About Ben Palmer

Ben Palmer is Chief Conductor of the Deutsche Philharmonie Merck in Darmstadt, and Founder and Artistic Director of Covent Garden Sinfonia, one of London’s most dynamic and versatile chamber orchestras. As a guest conductor he works regularly with the Hallé, BBC Singers, the Orchestra of Opera North, and Grimethorpe Colliery Band. Other recent guest conducting engagements include the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Royal Northern Sinfonia, the Orchestra of Welsh National Opera, London Mozart Players, NDR Radiophilharmonie, Deutsches Kammerorchester Berlin, and Sinfonietta de Lausanne. In the 2019/20 season he will conduct the Hong Kong Philharmonic, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, BBC Concert Orchestra and Heidelberger Sinfoniker for the first time, and return to the Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen, St Petersburg Symphony Orchestra, Deutsches Filmorchester Babelsberg, Pilsen Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, and Czech National Symphony Orchestra. He is one of Europe’s foremost specialists in conducting live to film, and is sought after as a composer, arranger and orchestrator. He is more than three-quarters of the way through his lifetime ambition to conduct all 107 Haydn symphonies.

www.benpalmer.net

@conductorben (FB, Twitter and Instagram)