Guest Blog with David Barton

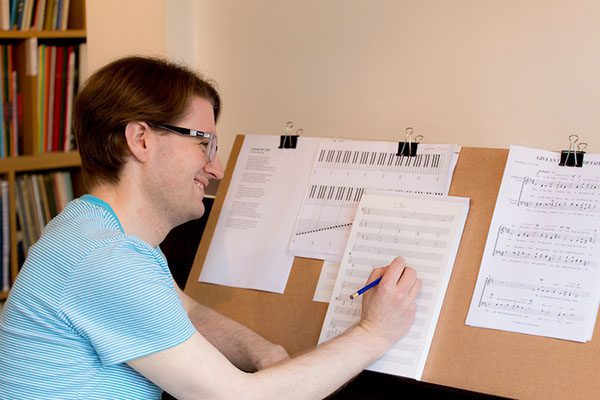

This month, David Barton shares his top tips on how to write for choir. David is a composer, arranger and private piano, flute and singing teacher based in Lichfield. He has composed a number of choral and instrumental works and was shortlisted for the Inspiration Award in the prestigious 2018 Music Teacher Awards for Excellence.

1. People are not organs – they need to breathe!

The criticism often levelled at the English composer, Herbert Howells, is that he wrote for voices in the same way he wrote for the organ. I think that’s a bit harsh, but it’s a valid point. When you’re writing for choirs, think about the breathing. Will all the parts breathe together? Will the text make sense with the physical demands of singers needing to breathe?

We don’t normally mark breaths in choral music, but it’s definitely worth doing so if you want singers to breathe in a particular place, and it’s somewhere which might not be immediately obvious to them.

2. Think horizontally, as well as vertically.

When we’re composing, we can get a bit bound up in chords and harmony, but when writing for choirs, although we hear the sound as a whole, each singer will sing (and learn) their part independently as a line of its own. I always try and make my individual lines just as singable as the line of the voice part which has the main tune. Altos don’t want to suffer another part which is only written on two notes. Play or sing each part independently. Singers will be grateful for having a memorable line to learn and sing.

Watch this video of the alto part from Eric Whitacre’s The Seal Lullaby:

As alto parts go, it’s pretty interesting (and they even get the tune!)

Now listen to it in the context of the whole piece. It is the interweaving of the horizontal lines which creates the vertical harmony.

3. Choirs don’t have to sing words

When we’re composing for a choir, I think it’s automatic to think of singing text, but remember, voices can be wordless. Sometimes, it can be effective for one part to sing the tune whilst the others hum, or ‘ah’, or ‘oo’. There are some pieces which have no words at all: Delius’ Two Songs to be Sung on the Water is a good example. Other composers have also engaged singers in speaking, making percussion sounds, and even whispering. Have a listen to Ernest Toch’s Geographical Fugue:

4. Offer flexibility in voicing

Choirs are all different. Where previously, most choirs were SATB as standard, this isn’t always the case. More music is being composed for SAB choirs (which reflect the shortage of tenors). My setting of Christina Rosetti’s poem Remember is scored for SAB and piano. Think about the flexibility you could offer choirs; for example, rather than writing something for SA voices, write it for 2-part voices (which means it could be equally suitable for TB, ST, AB, SS, AA voices etc. Two -part festival by Tim Knight is such a piece, offering 2-part flexibility.

5. Get involved with a choir

The best way to learn to write choral music is to sing in a choir. Once you start singing choral music on a regular basis, you will appreciate all too well some of the challenges composers (and singers) face. You could also compose initially for a choir with whom you are involved. It’s a great way to try out your ideas to see if they work in practice.

You can find out more about David Barton here.

If you’re interested in listening to more of his compositions, why not subscribe to David Barton’s YouTube channel?